Jump to:

Recent Works:

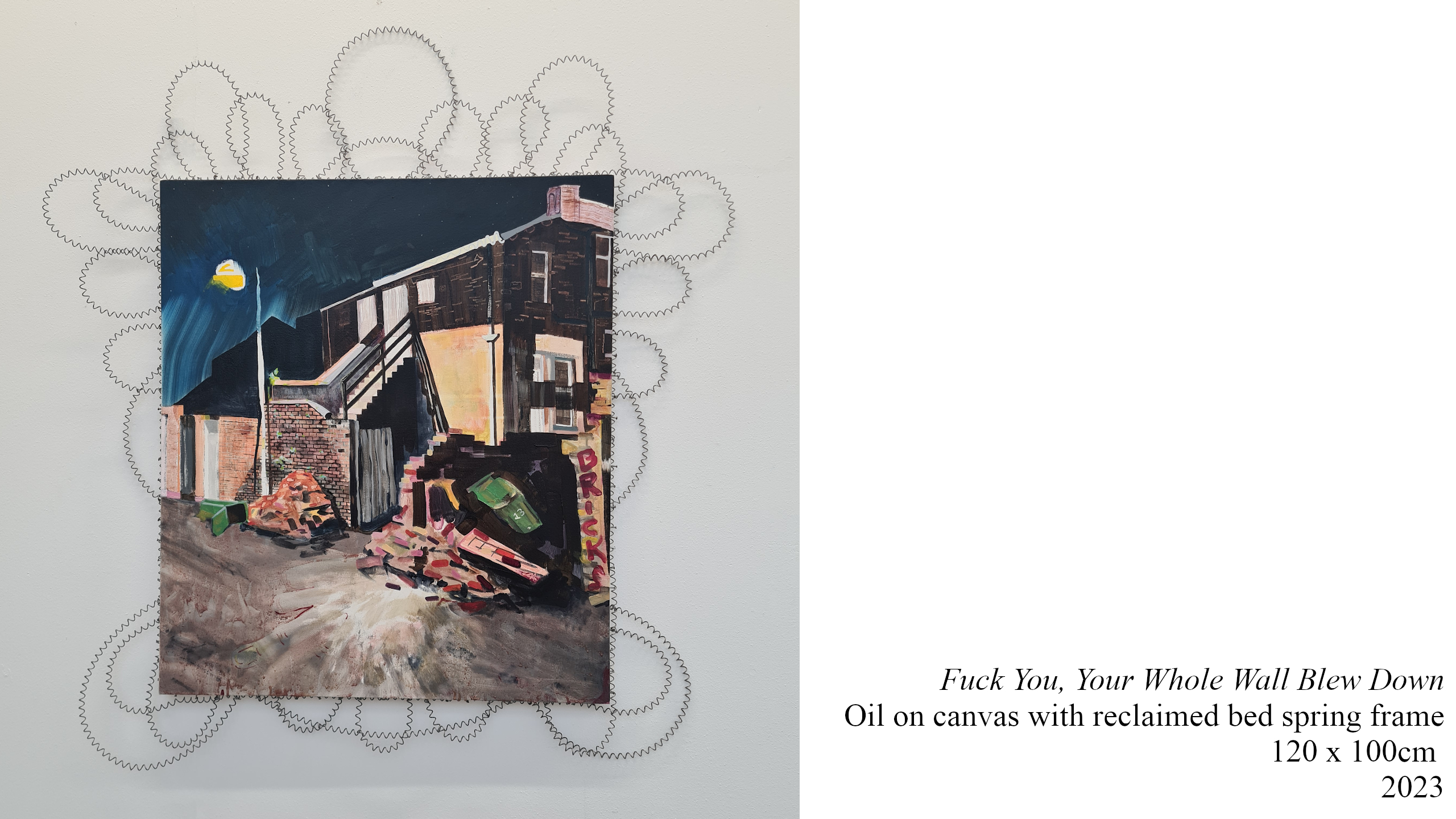

Oil on canvas with reclaimed bed spring frame

120 x 100 cm

2023

Scottish Histories:

2024

2023

2023

2023

2023

2023

2023

Different Histories:

2022

The painting is composed in two halves, divided along the line of the descending divine hand. Elizabeth's fruitless line to the left, and Mary's fruitful line (her son James I and VI would later assume both the English and Scottish thrones). The multicoloured thread pattern is an illustration of a twill weave pattern, used to make tweed. The thread colour deteriorates into single brushstrokes as you move from left to right. Symbolically alluding to the ultimately deadly struggle between these cousin monarchs.

The Queer History Painting: The Executions of Antonio Salomón and Antonio Ginovés/Baresa/Varesa.

Oil on canvas with gold wire frame

190 x 125 cm

History:

April 27th 2021 marks the 500th anniversary of the death of Ferdinand Magellan, who organised the first circumnavigation of the globe. He died during the Battle of Mactan, a failed offensive against native Filipinos who refused to give tribute to the Spanish king.

This April 27th 2021 also marks the 501st anniversary of disappearance/death/murder of the ‘grumete’ (common seaman) Antonio Ginovés/Baresa/Varesa, his surname is unknown and variable. He was aboard the Victoria, the only ship from the original fleet of five, to complete the historic circumnavigation. Five months previous, whilst drifting in the Atlantic doldrums, the Master of the Victoria Antonio Salomón was caught sodomizing Ginovés. Magellan presided over the trial hasty conducted at sea and sentenced Salomón to death by strangulation on the shores of what would later become Rio de Janeiro. His execution was carried out on December 20th 1519, in the shadow of Sugarloaf mountain, and was the first of many ordered by Magellan, who struggled desperately with mutiny throughout his expedition. Ginovés is thought to have been too young to stand trial and was himself initially spared. However, after months of ridicule Ginovés went overboard off the coast of San Julián, Argentina. It may have been suicide or murder.

Seven months later Magellan would find and name the Pacific Ocean.

On September 6th 1522 the Victoria returned to Spain, having completed her momentous pioneering journey. Only 35 of the original 270 crew lived to return to Spain.

Painting:

The painting is divided into three distinct panels.

On the left we can see the execution of Antonio Salomón on the shores of Rio de Janeiro. Salomón is kneeling on the sand, his neck wrapped in a lurid yellow rope which is held by two figures. One stands on the beach with Salomón. The other, in the top left, floats above the scene and has strange looking legs. His legs are a copy of the Ain Sakhri Lovers, the oldest known depiction of two people having sex, an Epipalaeolithic stone carving found in a cave near Bethlehem. His face is heavily abstracted, covered in a heavy green mask, an illustration of the hood which is often worn by an executioner. To the left of Salomón you find Rio de Janeiro Bay in which the Victoria is anchored, crowned by Sugarloaf Mountain. In the immediate foreground the sands part to reveal a hellish portal, through which a skeletal hand reaches and grabs the condemn Salomón.

In the central panel, we find a female figure facing to the right. She emerges from the shadows of the panels either side of her and is heavily patterned in cream and green. On closer inspection, you may notice that her patterning mimics the ex-mattress wire frame that surround the painting. One of her hands carries over onto the right-side panel and holds a ribbon onto which the details of this history is recorded. I have described her previously as a personification of either justice or the sea.

The right-side panel contains the ribbon and one obscured figure, our Antonio Ginovés/Baresa/Varesa. The lower half of the figure is consumed in blue water in reference to his death by drowning. Whilst the top half of the figure is partial obscured by a literal white wash. A receding pink/sandy pattern carry the eye up and away, creating one of the many distorted perspectives on this canvas which help create a dynamic composition that never decides whether it is coming or going.

The White Ship Disaster

Oil on canvas

150 x 180cm

On November 25th 1120, 901 years ago, a Norman ship sank off the coast of France killing approximately 300 passengers from every level of society. The White Ship, similar in design to a Viking long boat, hit a well known tidal hazard in the early hours of the winter morning because her captain, crew and many guests were drunk. Prior to boarding Prince William Æthling, King Henry I's heir, had ordered a wine fuelled party on the beach to celebrate his recently granted lordship over Normandy. As the boat first took on water William was bundled in the only life raft by his bodyguards. They got clear of the sinking wreck only to turn back around on William's orders to save his half-sister Matilda, who allegedly screamed insults at her brother as he rowed away. In no time William's ship was over run by desperate bodies fighting to float in the sea water whilst wearing heavy winter clothing. By morning only Berold, a butcher from Rouen survived by clinging to a rock. He recalled how the ships captain, Thomas FitzStephen, who initially survived by clinging to the ships mast, let himself drown on hearing that Prince William Æthling was dead, rather than face the wrath of his father King Henry I. The disaster directly resulted in a succession crisis and a period of English history known as the Anarchy, as William's sister Empress Matilda and his uncle King Stephen fought an 18 year civil war for England's throne.

The centre of the painting is composed like an hourglass. On the bottom half a blue seascape reaches out towards the viewer. Carved into the paint you spot two sinking ships, the larger one with a billowing white sail. Around the vessel agitated brush marks and smaller scratches illustrate humans, who are dwarfed into insignificance by the ocean. The muddy top half of the hourglass bleeds into the scene like inclement winter weather. The frame was designed to draw your eye to just above the centre of the hourglass motif, to hopefully then be pulled down/forward again across the tumultuous seascape. In response to a rainbow I photographed over the North Sea, during a walk from Seaham to Hartlepool, I completed the frame with a variety of high key colours. The lack of variety within the hourglass motif contrasts with the excited background, drawing further attention to the bleak sea tragedy taking place on the canvas.

https://thehistoryofengland.co.uk/blog/2021/07/04/320-justice-and-the-state/

I first heard of this particular history through my favourite podcast: 'The History of England'. I sent an email of my work to David, writer/voice of 'The History of England', and he gave me a shout out on episode 320. Which I very much appreciated and made me smile.

North East History Paintings:

Oil on canvas with reclaimed bed spring frame

120 x 100 cm

2023

2022

Amazingly, I was able to find images of his grave on the remarkable website https://lonelygraveswa.wags.org.au which hosts a visual catalogue of various isolated graves found across Western Australia. The pine board was recycled from my childhood kitchen worktops, which fits.

Oil on canvas

68 x 50cm

2022

Her father, the Reverend R Cooper, was a huge character in the history of Robin Hood's Bay where he led the church for 56 years. He had 5 children, who all died childless, most of whom lead remarkable and sometimes tragic lives of their own. This is the first of a series of works looking into this Victorian family who grew up within the exact same walls I grew up in.

How great to find out that I wasn't the only painter fostered within these walls.

Thorpe Lane, Robin Hood's Bay (1920's)

Oil on canvas over board

50 x 70 cm

2023

Inspired by an old sepia photo this was an experiment in colouration and trying to create depth in a landscape. I initially thought the figure in the foreground was carrying two pails of milk. However, when I shared this painting and its source image on a local Facebook page someone suggested that they could be pails of paraffin which I guess would have been used for lighting.

Venerable Bede's account of the conversion of King Edwin of Northumbria, 627 AD

Oil on canvas

120 x 150 cm

2021

Venerable Bede was a monk, historian, author and teacher who lived near Jarrow in around the start of the 8th century. He wrote the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, the first account of Anglo-Saxon people ever written. Bede is nicknamed the 'Father of English History'. He wrote the following when describing the conversion of Edwin King of Northumbria to Christianity in 627. Bede writes from the perspective of one of Edwin's chief advisors:

"The present life of man upon earth, O king, seems to me, in comparison with that time which is unknown to us, like to the swift flight of a sparrow through the house wherein you sit at supper in winter, with your ealdormen and thegns, while the fire blazes in the midst, and the hall is warmed, but the wintry storms of rain or snow are raging abroad. The sparrow, flying in at one door and immediately out at another, whilst he is within, is safe from the wintry tempest; but after a short space of fair weather, he immediately vanishes out of your sight, passing from winter into winter again. So this life of man appears for a little while, but of what is to follow or what went before we know nothing at all. If, therefore, this new doctrine tells us something more certain, it seems justly to deserve to be followed."

The flight of a house sparrow becomes a metaphor for life itself. We, as historians or artists, peer from the afterlife back through a luminous Anglo-Saxon hall. Tiling inspired by Tintoretto's 'Washing of the Disciple's Feet' found in the Shipley Gallery, Gateshead.

Gateshead History Painting: The Murder of Price Bishop William Walcher. The Second Harrying.

Oil on canvas

120 x 170 cm

2021

On the fourteenth of May 1080 William Walcher, the Prince Bishop of Durham, was chased into a Anglo-Saxon Gateshead church by a mob of vengeful locals. Accompanied by a retinue of one hundred men, close to the site of St Mary’s visitor centre, Walcher’s refuge was soon set ablaze. Many men were burnt to death inside and Walcher himself was cut down as he attempted to flee. In response, William the Conquerer sent an army to harry the north for a second time.

Macbeth, William, Malcolm

Oil and oil pastel on canvas and printed acrylic silkscreen on lightbox

185 x 155 cm each

Macbeth, William and Malcolm' is a triptych. I made the central panel some birthday celebrations- which I am happy about because I get to remember the Dingle whiskey Mum bought me forever more when I see this painting. It is just an abstracted battle scene (quite messy and drippy and evocative of chaos and violence). To give the work structure I penciled in the neat bright yellow frame. Which I set against a pink-black-white-translucentgreen background because I like those colours. I finished it by writing the title of painting across the painting. Subtly though. It's quite effective.

Anyways, the panel on the left is inspired by Macbeth. I decided on him after we went to his burial place in Iona. The heath scene works by providing the setting of 'Gateshead Fell'. I like some of the big brush strokes as they are satisfying to see - but I also like the purply-blue palette cause I have never really worked in those colours before.

On the other side I had an image in mind:

When I was at university I came across The Palace of Westminister's 13th century 'Painted Chamber'. Commissioned by Henry III, the chamber was said to be known across Europe thanks to its beauty. But they faded over time and got whitewashed over. Then were rediscovered and partially restored. Then the Burning of Parliament happened, so they're gone gone. 🙁

But,

Fortunately, two artists got in there to copy. And I managed to find one set in the Ashmolean, the others are in the British Museum. I arranged to view the watercolours in the private library and managed to take some pictures - however, I should have taken more..

Anyway, I digress.

The panel on the right is a copy of one of the scenes that used to hang in the Painted Chamber. A quick, fun, bright, expressive copy. Cause thats the fun bit. I later found out that Malcolm III - heir to murdered King Duncan (Macbeth) - also the Scottish King who was defeated by William the Conqueor on Gateshead Fell in 1068 (central panel) - was buried in Tynemouth Priory, near Helen's house, near my studio. So I decided that the right side panel could be about that. I am going write a little sign saying 'Malcolm III was buried at Tynemouth Priory', that'll do the job.

Source: E-mail to Beryl Pollard.

The Lambton Worm

Oil on canvas

75 x 60 cm

2020

This is a painterly landscape, focused on a black drawing of Penshaw Monument, an iconic early Victorian folly found near Washington, County Durham. The painting is playful and abstract and shows a variety of worm-like brush strokes converging on the elevated monument. The painting references local folklore which recounts a grotesque giant worm that once wrapped itself around the iconic monument, only to be vanquished by a local hero. I cannot elaborate much more. This is a fun image.

Gateshead History Painting: The Murder of Price Bishop William Walcher

Oil, spray paint, oil primer and wax on canvas

80 x 100 cm

2020

On the fourteenth of May 1080 William Walcher, the Prince Bishop of Durham, was chased into a medieval Gateshead church by a mob of vengeful locals. Accompanied by a retinue of one hundred men, close to the site of St Mary’s visitor centre, Walcher’s refuge was soon set ablaze. Many men were burnt to death inside and Walcher himself was cut down as he attempted to flee. In response, William the Conquerer sent an army to harry the north for a second time.

Gateshead History Painting: Murder of Prince Bishop William Walcher illustrates Walcher’s final moments within a hectic and fractious composition. Outside of a central figurative panel the painting ruptures and decomposes into abstracted gestures and plains. For me this alludes to the confusion and inherent corruption our histories undergo over time. Walcher’s life and death has been largely forgotten in the last millennia, not even making it onto the history section on Gateshead’s Wikipedia page.

Within the central panel the audience can see a startled Walcher fleeing from flames wearing a bright red tunic covered in a repeated motif of goat’s heads. Through this dress, the figure of Walcher becomes emblematic of Gateshead. The town was first mentioned in Latin translation in the Venerable Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People as “ad caput caprae” (“at the goat’s head”) and this symbol is still widely used today. Whilst history is constantly eroded by time it is also reborn through document creation and re-representation. William Walcher and the history Gateshead are forever intertwined. This is his/story.

Accompanying text to an unsuccessful submission of this painting to an Open Call exhibition 2020.

The Great Fire of Gateshead and Newcastle

Oil on canvas

200 x 167 cm

The Great Fire of Gateshead and Newcastle was caused by a massive explosion on the Gateshead Quayside. The precedeing fire had brought thousands of local spectators onto the shores of the Tyne. 53 people were killed. Miners in Monkwearmouth colliery, the deepest in the country and 11 miles away, heard the explosion and came to the surface, concerned as to the cause. Trains ran to Stephenson's new High Level brigde direct from London for days afterwards, just to catch a glimpse of the carnage. This all happened where the Sage stands today.

You can find:

St Mary Church, Gateshead; the Georgian Tyne bridge; th High Level, St Nicholas Cathedral, All Saints’ Church, Grey’s Monument.

Source material: handcoloured woodblock engraving from Illustrated London News, 14th October 1854: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_fire_of_Newcastle_and_Gateshead#/media/File:Newcastle_and_Gateshead_Great_Fire_1854_-_Illustrated_London_News.jpg.

Gateshead History Painting: The Gibbeting of Highwayman Robert Hazlett

Oil, acrylic and oil pastel on canvas. Framed with copper piping and black fringe

130 x 210 cm

“The other attachments you received, instead of the goaty Portrait of Joseph Swan, is called: Gateshead History Painting: The Gibbeting of Robert Hazlett, which also has a good story.

(This one, and the central panel of the triptych are in my bedroom, which makes it very decadent. I also found a nice dark wardrobe in the back alley the other day which had been left for scrap. So I have that now aswell. I am writing this sat in my bed next to a massive pile of washing I really don't want to fold)

Robert Hazlett was a highwayman who was executed and placed in a ceremonial gibbet for six years. Again, this happened in the local area, it all took place by the hospital I volunteer at actually. Hazlett hung there for so long that a small marshy pond that was by the sight was renamed informally as Hazlett's Pond. This all happened 250 years ago. Not that long ago. The pond has since been drained and a children's playground sits on the former site. Isn't that so ghostly and brilliant. When it rains, does the playground flood, reforming a small pond? Yes. Someone told me that after I posted a picture of the painting on the internet. I first made that the background painting in first year at uni. It's a nice pattern. I just added a corpse and some words to push the audience towards that particular story - which I think is fascinating. Which is why I am starting to write them down in an easy to read way on my website. I think the story compliment the paintings. It was already unstretched so I turned it into a flag because I couldn't afford the wood to stretch it at the time. And it's just easier to store and own in the long run.”

Source: e-mail to Beryl Pollard:

A Portrait of Joseph Swan

Oil, oil primer, emulsion, thread and pheasant

feathers on canvas. With two copper horns

190 x 150 cm

A Portrait of Joesph Swan is still in the works. Alex bought me some canvas for my birthday because he is a great big brother. I was a little anxious about what I was going to put on it, because I had no idea. So I just started to chop it up with some scissors because I had recently watched a documentary about Alexander McQueen. And he was so great with scissors, I felt I might as well give it a bash. I know this is a bit eccentric, but I try to have fun when I make paintings, it entertains me. What emerged kind of looked like a goat, which is good, because Gateshead may have been named Gateshead because of the bastardisation of the place name 'goat's head' in the early 8th century. So its good to get a goat in the picture. I whited out an area and left it. I went on a walk to visit Joseph Swan's house just up the road from my house. That house was the first house in the world to be illuminated by electric light because Swan invented all that. At exactly the same time as Edison actually.

I think that is an extraordinary history to live around and I make history paintings. Conveniently swans are white and I had just put white on this goat. Before you know it you've made some copper horns and bought hundreds of peacock feathers (another McQueen reference) and made what you can see here in this email today. It is a bit weird. But it is good fun - Helen likes this one. It's not finished yet, still got a little way to go.

There is also something Stubbsian about the swan.

Irish History Paintings:

Irish History Painting: The Death of Turgesius

Oil and pencil on canvas

70 x 80 cm

Turgesius was an Viking Chief active in Ireland in the 9th-century. He also credited by many as founding the city of Dublin. He was killed in 845. There are conflicting reports into his death. Under the order of Máel Sechnaill I, King of Meath, Turgesius was either drowned or assassinated by 12 beardless young male warriors disguised as a wedding party. Abbreviated here to the "Twelve Killer Drag Queens".

This painting evades resolutions. Like the history itself, the central plain is a murky wash. Muddy water? Couple with the curved text the viewer is reminded of theatrical posters. graphical advertisement to a distant, lost history. I remember thinking a lot about the function of contemporary history painting acting as historical signage, seminar-inspired. Which I still occasionally Wikipedia. (I later had stimulating conversations with Samson about intentional composing paintings that don't centralise. Is there an anarchic quality to that perhaps?)

Outside this barren central panel I make reference the graphic design of Tadanori Yokoo: in particular his macabre 'A Climax at the age of 29'. A vibrant Japanese sunburst motif centres on a floating reclining figure. On closer inspection he is supported by three golden threads. The figure is based upon Jacque Louis David's 'The Death of Marat'. David: the father of history painting. Turgesius is dead, so a body hangs at the bottom of the frame. As it says, this is Michael J McCormack painting.

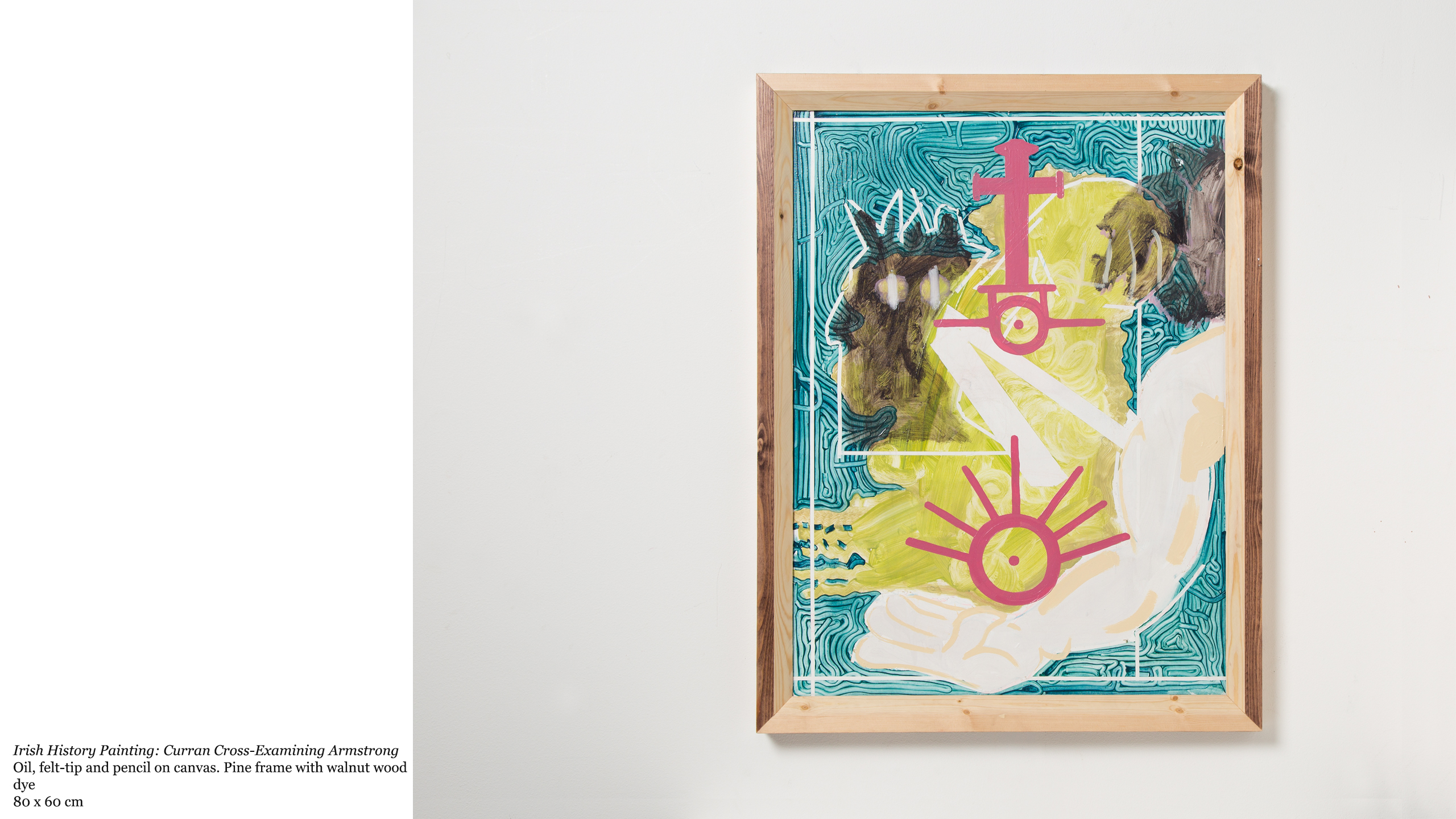

Irish History Painting: Curran Cross-Examining Armstrong

Oil, oil primer and pencil on canvas. With pine frame and walnut wood dye

80 x 60 cm

The title refers to a controversial court case in Irish history. A case that ended in the execution of the John and Henry Sheares, both former barristers, both United Irishmen in 1798.

The title is important in this one and it is Irish History Painting: Curran Cross-Examining Armstrong. The imagery stays very close to those words. In the background you can see a large textured green Ireland. It is surrounded by swirling mass of teal(?) brush strokes. Above Mayo and Galway there is a dark shadowy figure. A humanoid character. Spreading SE two crisp white lines lead to another predominately white object. On second glance you recognise this as a large arm, with an upturned palm, cradling the Irish south coast. This is Armstrong. There is a bicep there. Being examined by the other figure. The painting has been reduced to pun. Which hopefully still generates a vague sense of narrative and maybe action. Providing structure across the canvas there are many sharp narrow white lines. They both frame the who piece and etch out an impression of a punching figure. Northern Ireland is the fist. Overlaid, on top of it all, are two large pink symbols. One floating above centre, one floating below. They are from a map that I can no longer find. But I am quietly confident that they are symbols from a Cromwellian map of Ireland that I found in the Bodlein collection. One, I think the lower one, was the symbol for a town razed to the ground. I roughly marked then out in pencil on the map. I forget what the top one is – perhaps a rebel controlled town? There is also another dark smudge on the right-side of the canvas, providing a buddy to the shadowy Curran, and providing a visual counter-balance. It's all about making good looking and compelling images at the end of the day. Always. The frame is partially stained with walnut oil.

Irish History Painting: Kildare “On the Necks of the Butlers”

Oil on canvas. Pine frame with walnut dye

100 x 75cm

This one is another pun-based composition. Quickly done. There is a sketch of some butlers, white gloves, bowties, and there is a crude figure standing on their necks. The torso of which contains an oak tree, which refers to the next painting in the series: Irish History Painting: The Oak of Kildare. Again, another pun painting. The framing is also quick and experimental. Both the internal transparent blue border, and the single splinter of wood hanging off the bottom right hand corner of the canvas. I think it is clean and sharp next to the pink smudging it sits alongside. I seem to think that the neat contrasts can be useful for good viewing. I no longer have this painting.

I never uncovered the related histories.

Irish History Painting: The Oak of Kildare

Oil and board. Glitter plastic frame with plasticine

33 x 23cm.

This is a quick sketch of an oak tree surrounded by a sheeney glittery plastic frame. A laptop casing that didn’t fit and was repurposed. I enjoying experimenting with framing. Again, this is a reductive and very neutral and symbolic history painting. This series generally sees me gently prod at the boundaries of what could constitute a history painting – I was thinking about concepts around signage/documentation after a chat with Anthony. Always a great tutorial. I gave it a little black modelling clay frame that was never going to last.

Again, I never uncovered the related histories.

Irish History Painting: Nial and his Nine Hostages

Oil on canvas with oak and walnut through-wedge mortice and tenon frame

125 x 95cm

2018-21

History:

This work draws from the folkloric figure of king Niall Noígíallach. Legend has it that Nial succeeded in becoming one of the first High Kings of Ireland when he conquered all nine provinces. He held a high-born hostage from each territory to ensure fidelity towards his crown. Further to this Nial was allegedly the invading pirate king who stole and enslaved the young Welshman who later became St. Patrick. And his son, Loégaire, was the same wicked druid who St Patrick converted during a supernatural/miraculous battle on Tara hillside. I'm not sure I ever exhibited those painting together?

Artwork:

The larger Irish History Painting series explores how a contemporarily-made history painting could/should/would function and present today. In Irish History Painting: Nial and his Nine Hostages the artist reduces the fable of king Niall Noígíallach to its bare bones in an abstracted infographic manner. Nine flesh toned circles crowd around a larger crowned circle in the centre of the canvas. Composed around this central motif nine arrows project outwards in various directions: alluding graphically to escape. Celtic motifs can also be found capping bold horizontal brushstrokes in the background.

Irish History Painting: The Burial of King Dathy in the Alps, his thinned troops lay stones on his grave.

Pigment, oil, hard pastel, charcoal and pencil on canvas. Pine and plywood stand with walnut wood dye, polyester, pin nails and pen.

137 x 38 cm

I built a stand for this painting to bring it to a human scale, trying to facilitate a more personal viewing experience believe it or not. At the top of the canvas there is a sketched Alpine landscape, grey purple mountains in the background, rolling green fields in the foreground. Within this scene we see small stickmen laying funerary stones, like ants around a pair of exposed feet. There are small white flowers, and a shallow sense of depth, created by the receding stack of warm stones. Under this panel is a huge red swirl. Bright, vibrant and possibly violent. Uniform sky blue brush strokes button above the red swash creating depth and structure. This is accentuate by a thin white ribbon, that runs centrally throughout the who painting, foregrounded by a central crest. With Daffy duck in it. When you read ‘Dathy’, in an English accent you might sound out ‘daffy’, like I initially did. The Irish read the same word as ‘Dah-hee’. Read into that what you will? Sometimes it’s good to be off the mark.

Legend has it King Dathy was killed by a lightning strike.

Irish History Painting: Ormond refusing to give up his sword

Acrylic, oil, poster paint, soft pastel and pencil on linen

80x60cm

History:

This work focuses around James Butler, 1st Marquess of Ormond. Ormond was a fierce royalist and stood on the side of the crown against Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell’s bloody invasion of Ireland in 1649-50. Earlier in his career Ormond was summoned to parliament to speak about bubbling unrest in Ireland circa 1634. Due to the unrest peers were ordered to relieve themselves of their arms prior to session. Ormond famously refused, seeing the request as a slight on both his honour and the honour of his Irish subjects, and kept his sword on his person always.

Artwork:

Irish History Painting: Ormond refusing to give up his sword explore the role of story-telling and humour in contemporary history painting. Ormond is represented as a large middle finger defiantly opposing two pencil-drawn agents who have been ordered by a bearded figure (right-side of the canvas) to collect his sword, found near centre. The action all takes place behind a theatrical curtain border heightening the humorous pantomime of this bizarre history. Narrative is followed simply as the viewer is encouraged to follow a soft blue arrow which loops from the bearded figure round to the central sword.

Irish History Painting: James' Entry into Dublin

Oil and soft pastel on canvas

144 x 92 cm.

James II was the King of England and Ireland for three years in the 1680's. He was the last Catholic monarch of England, Scotland and Ireland and was deposed during the Glorious Revolution. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II and her Dutch husband William of Orange. Shortly after the revolution James entered Dublin with a small retinue of men, under two thousand. The Irish remained loyal to James and supported him in his upcoming Battle of the Boyne. Which he lost.

James fled back to exile in France shortly afterwards, abandoning the Irish to fight on against William of Orange without there king. James II became known as Seamus an Chaca, which apparently translates to James the Shit. (If any Irish speaking friends could fact-check this for me I'd appreciate it).

James' entry to Dublin was a vapid/hollow affair. You can see bland grey bunting, a barren featureless landscape and an arrow pointing to a shit stain on the horizon

Irish History Painting: The Death of St Ruth.

Oil on canvas

130 x 66 cm

This painting marks the moment Charles Chalmot de Sainte-Ruhe (St Ruth) was decapitated by a rogue cannon ball. On the 12th July 1691 St Ruth was leading the Jacobite army at the battle of Aughrim, Co. Galway. He fought successfully against the Williamite forces for several hours, inflicting heavy damage, helping make this one of the bloodiest battles ever fought in the British Isles. That was until a stray cannonball found its perfect target. After St Ruth's explosive death, the Jacobite forces become disordered and the tides turned. Soon thousands of their forces were also dead, and the Jacobites lost the pivotal battle. Another one.

The painting was partly inspired by Quentin Tarantino's 'Kill Bill' films which I was watching at the time. Violent and theatrically bloody I wondered if I could achieve similar results in painting. On the top half of the canvas a green sketch of the reconstructed battlefield of Aughrim is inudated with a wash of blood. On closer inspection a faceless outline of a figure falling, just below the green battle scene, is the source of the flood. This figure floats above two white copies of the Irish map. Scanning further down you find the reminents of a book motif from a previous composition. And a series of pastel columns that were added to provide a calmer contrast with the action above. In the centre of this column you can see a white cockade, a fashionable ribbon that was worn by those in favour of a Jacobite restoration.

Figurations:

Janus

Oil and spray paint on canvas

70 x 100 cm

Janus was a Roman God with two faces who has been painted/sculpted/cast/drawn countless time over millennia. He gave his name to our first month January. He was the god of transitions, time, beginning and endings, frames, gates and doorways and duality. With that in mind I made this.

Landscapes:

2022

Amazingly, I was able to find images of his grave on the remarkable website https://lonelygraveswa.wags.org.au which hosts a visual catalogue of various isolated graves found across Western Australia. The pine board was recycled from my childhood kitchen worktops, which fits.